Starting and growing a platform

Starting a platform is a chicken-or-egg problem because either side of the platform may be waiting for the other side to join. A social network with only writers and no readers cannot take off. A ride hailing network with only riders and no drivers is not viable. The Windows mobile phone platform never took off because users were waiting for app developers to develop apps, and app developers were waiting for users to start using the system.

The trick is to get the attractive side of the platform on board first, after which the other side will join, attracted by the attractive side.

For example, Amazon started a retail shop first, which attracted consumers. It then transformed itself into a marketplace by opening its infrastructure for third-party sellers, who were attracted by the consumers already using the platform.

Facebook used another strategy. It was open to students only, a subculture wildly interested in who else is on the platform. After enough students had joined, it opened to anyone with an email address. Users outside academia had heard of this new thing called Facebook, and they were attracted by the buzz.

Here are some strategies for getting initial attractors on a platform [1].

- Monetize your infrastructure: Amazon started a retail site first, opening to sellers when there were enough buyers. The buyers attracted the sellers.

- Single-sided service becomes multi-sided communication platform: OpenTable provided booking management services to restaurants first, before allowing customers to book.

- Simulate the attractors: Reddit started by posting a large amount of content from fake profiles, which attracted people to the site.

- Stimulate the attractors: Medium started its curated content platform by paying high-quality contributors. This attracted readers, who then also started to write.

- Start in a niche where the need is high: Facebook started as an exclusive communication platform for university students. This attracted more students, eager to know who else was on the platform. With sufficient size, this also attracted normal people.

- Exploit existing networks: Airbnb spammed hosts who listed on Craigslist to list on Airbnb as well. And it offered a listing on Craigslist to anyone listing on Airbnb.

- Exploit existing attention: Twitter displayed messages on stage at the SXSW festival, which captured the attention of important influencers, which attracted lesser-known people.

- Apply force: The procurement platform Ariba asked large customers to force their customers to use Ariba. It then provided additional services for smaller customers, which attracted more customers.

Once users are on board, the platform needs to grow further. It is now important to exploit network effects. A network effect exists if the value of joining the platform depends on how many other users have already joined the platform.

Platforms may have positive or negative network effects, which affect growth in opposite ways.

If the value of the network increases when there are more other users, then we have a positive network effect. For example, a social network has more value when more people are using it. A telephone network has more value when more users have a telephone.

If the value of a platform decreases when it has more users, then there is a negative network effect. For example, the value of using a road network depends on how many other people are using the roads. The more people are using the roads, the less value the network has, because there will be more traffic jams.

An example from the digital world is the email network. When more and more people and companies started using email, the number of irrelevant messages skyrocketed. There is a positive network effect for senders but a negative network effect for receivers of email. To be able to grow, a platform must have positive network effects. Once the number of users has reached a tipping point, the network will grow organically because existing users will attract more users. What happens next depends on three further conditions [2].

First, the platform must not be interoperable with other platforms. For a utility platform this means that apps developed for the platform do not run on other platforms without additional work. For example, Android apps do not run on iOS without additional work. They must be developed for each platform separately [3].

For connection platforms, a lack of interoperability means that users of different platforms cannot connect with each other. Without interoperability, each platform supports its own value network. Social networks are currently not interoperable. If users of one social network want to connect to users of another network, they must first join the other network. This is an important force of growth of social networks.

This contrasts with telecommunications networks. All telco providers can interconnect, so subscribers of one telco provider can connect to subscribers of any other provider. Payment networks have this property too: You can pay from any bank account to any bank account, regardless of the bank that sender and receiver use.

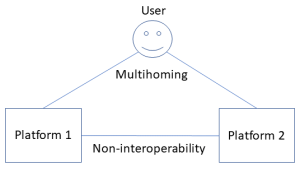

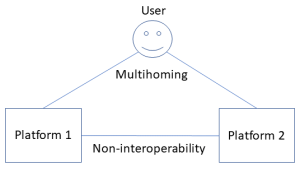

To summarize: If two platforms that offer similar services do not interoperate, then a user has the choice of multihoming (using both platforms at the same time) or using only one of them. If the user uses only one, then they can decide after a while to switch to the other one. Both multihoming and switching come at a cost. If both costs are high, then users are locked in the first platform that they use.

Second, multihoming must be expensive. Multihoming is using several platforms at the same time. For example, using two operating systems at the same time is expensive. People usually choose to use one operating system only. Most people stick to iOS or to Android and do not have a second smartphone with the other operating system.

Third, switching costs among platforms must be high. If two platforms are not interoperable and multihoming is expensive, then at any point in time, users will use one platform only. If it is also expensive to switch platforms, users will never switch platforms. They will stick to the first platform they chose. We see this mechanism in operating systems. iOS users tend to remain iOS users, Android users tend to remain Android users.

In contrast to operating systems, multihoming of social networks is cheap. Many people use Facebook, Twitter, and other social networks at the same time. If multihoming is cheap, then switching costs are irrelevant because people can use several platforms at the same time.

The result of all of this is that positive network effects and the lack of interoperability are the major forces of growth of digital platforms.

If multihoming is expensive and switching costs are high, this typically leads to oligopolies of a few large platform providers. For example, users of iOS and Android usually stick to the first one they chose, and rarely switch to the other platform. There is no room for yet another operating system because the cost for users of switching to a new one is much high than expected benefits.

If multihoming is cheap, users do not have to switch and there is room for new platforms that offer similar functionality. For example, TikTok has conquered the world by offering superior recommendation function for short videos, which attracted large numbers of young people to the platform [4].

[1]

These tactics are described elaborately by (Parker, et al., 2016) pages 89-99 and by (Reillier & Reillier, 2017) pages 93-97.

[2]

Based on (Eisenmann, et al., 2006)

[3]

See (Parker, et al., 2016) and (Scott Morton & Kades, 2021).

[4]

See (Brennan, 2020)